by Mitchell Brown, Reporter

A club is part of the lifeblood of a music scene. Without a club, a venue, bands are left to backyards and basements, and forget about touring bands coming to your city regularly without one.

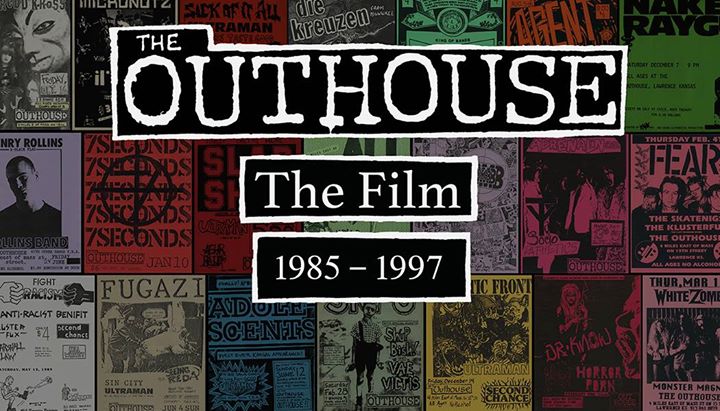

New York City had CBGB, Los Angeles still has the Whisky a Go Go and the Troubadour, Berkeley has 924 Gilman Street. The focal point of “The Outhouse: The Film, 1985-1997” probably had more in common with Gilman Street, in that it was a DIY space detached from the more traditional, established rock clubs.

Its location was physically removed from any happening downtown arts and entertainment district. The Outhouse was a cinder block building located on the outskirts of Lawrence, Kan. in the middle of a cornfield and was in operation from 1985-1993, then again in 1996-1997.

Its reach extended beyond a Kansas cornfield. The significance of The Outhouse becomes apparent when looking at the list of bands that played there, from testosterone-laced, East Coast hardcore, such as Agnostic Front, Slapshot and the Cro-Mags to the melodic pop-punk of Screeching Weasel, the Queers and Green Day. From ska to death metal, it all found a way into The Outhouse.

The anomaly of the subject matter makes for fertile ground for a decent documentary. Uncommon outliers catch our attention. Although The Outhouse was essentially “before my time,” I knew of its legacy.

In the past 10 years, a plethora of punk related documentaries have been released.

I think the impetus for a lot of said releases can be attributed to “American Hardcore,” the 2007 documentary about the rise of hardcore punk in the 1980s. The movie contained a pervasive focus on regionalism, with certain bands and cities getting more attention than others. The Midwest was treated as a footnote in the film

Brad Norman, the director of The Outhouse documentary, said “American Hardcore” was indeed an influence.

To date, “The Outhouse: The Film, 1985-1997” has been screened in 18 cities, including Washington D.C., Seattle and San Francisco. Norman said San Francisco was one of the best receptions, an additional night was added because the first night was a sold out screening.

Whenever I found out the film was going to be shown in Springfield, Mo. on May. 23, I made travel plans, and away I went, landing in a part of Missouri I’d never been to. The lobby of the Moxie Cinema in downtown Springfield resembled a punk rock reunion, with the sight of salt and pepper hair and inked up arms. The movie was brought to Springfield by Mike Martin, a lifelong Springfield resident.

“I heard the film was made, and I didn’t get to see it in Kansas City, so I thought, the Moxie, I can bring it here,” Martin said. During the heyday of the Outhouse, Martin would make the trek from Springfield to Lawrence.

When the movie started, a healthy sized crowd had packed the room, not quite to capacity, but close.

The plot of the movie was organized in chronological order, starting with the origins of The Outhouse via Bill Rich, contextualizing the birth of The Outhouse as an extension of what Rich was doing with his Fresh Sounds label and Talk Talk fanzine.

Early in the film, a heavy emphasis was placed on Lawrence localism, with bands like the Mortal Micronotz. Norman noted that some of the first people who agreed to be interviewed for the film were Roger Miret and Vinnie Stigma of Agnostic Front. He said they encouraged him in featuring Midwestern bands in the project.

Norman said he went to Wisconsin to interview Die Kreuzen, obtaining over an hour’s worth of footage, which didn’t make the final cut of the movie. He explained the selection of interview footage was based on relevance. The structure of the film is similar to other punk documentaries, in combining more recent interviews shot by the director and archival footage.

The talking head footage in the movie was made up of famous/infamous icons, including Henry Rollins, Ian MacKaye, Ice-T, Tesco Vee, etc. and local patrons and promoters. This balanced combination serves to de-emphasize the notion of the rock star and illustrate the lack of social barriers between bands and fans.

The idea that punk rock is about something more than music is displayed in the film, as details about the sub-culture elements were reoccurring. The story of how the disaffected found a connection via a club is prevalent. While the building provided a sense of salvation for wayward Midwestern youth, at the same time, The Outhouse was a thorn in the side of some of the local normals.

The neighbors who lived in a nearby farmhouse and a sheriff were interviewed. The addition of their perspectives provided a counterpoint, creating a well-rounded narrative.

For me, the highlight of the film was hearing insights from members of national touring bands.

The culture shock related to the club’s location expressed by Ice-T (his thrash metal side project Body Count played The Outhouse in January of 1993) and Angelo Moore and Norwood Fisher of Fishbone drew riotous laughter from the audience. Norman said when interviewing members of Fishbone he was tempted to leave the room due to laughing so much.

Henry Rollins pontificated on the geographical reasons why something as seemingly chaotic as The Outhouse could exist where it did. He attributed it to the geography of the Midwest, with more open spaces, as opposed to larger coastal cities with higher population density.

As far as punk documentaries go “The Outhouse: The Film,1985-1997” easily stands alongside “American Hardcore,” “Another State of Mind” and the 16 millimeter glory of “The Decline of Western Civilization.”

The growth of punk, alternative, indie music in the ’80s wasn’t a tale of two cities. It wasn’t just about New York and L.A. A number of points in between existed, homegrown scenes all over America, in which the participants were inspired by what was happening in the Big Apple and the Golden State, inspired by likes of Bad Brains and Black Flag to build a scene in their own backyards.

The story of The Outhouse is the story of one of those points in between.

“The Outhouse: The Film, 1985-1997” will be available for rent online this summer. For more, follow the film’s Facebook page here.