by Mitchell Brown, Reporter

The 1960s were an undeniably interesting time – the major events of that era invite so much retrospective research. It was a time marked by turmoil and change, which can be seen with the films, fashions and music of the time. Some of the icons of the ’60s became larger than life, names loomed and lived on through the years.

Charles Manson was one of those names, remembered for the terror his Manson Family disciples caused on a hot August night in 1969, as the remnants of the “Summer of Love” came crashing down. The slaughter shocked Los Angeles and the world, and Manson stayed in the public eye via prison interviews. Charles Manson was essentially the first celebrity serial killer for the television era, like a “rock star” of sorts.

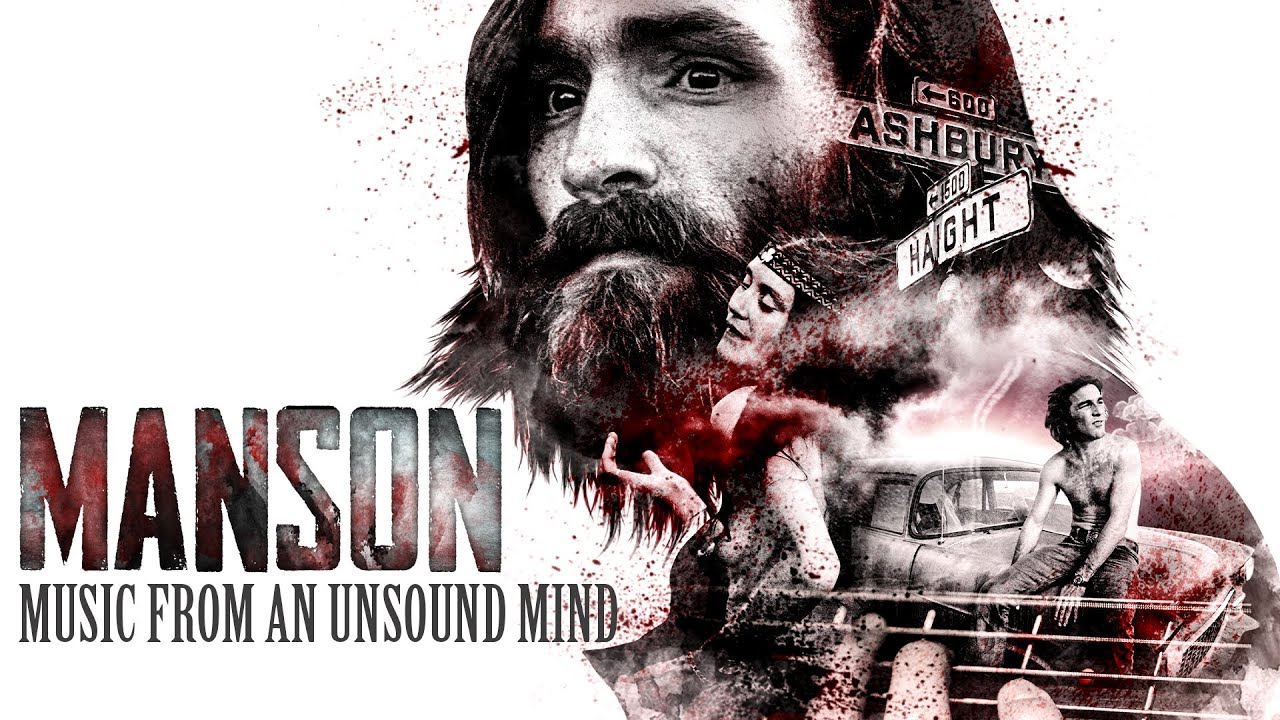

Making music was part of Manson’s life. “Manson: Music from An Unstable Mind” is a recently released documentary, now available on DVD and most online streaming platforms, that largely focuses on Manson’s musical side and his relation to the Californian counterculture of the ’60s. The film consists of an overview voiceover narration, interview clips spliced in between archival footage and audio of Manson in recording sessions.

Manson the musician stands in stark contrast to the image of Manson the murderous madman, yet the connection is inseparable. The two are one and the same.

The movie presents a retrospective view on the swinging ’60s. In 1967, fresh out of prison after a ten year bid, Manson made his way to San Francisco, as the counterculture had engulfed the Haight-Ashbury. Manson was 32, and he was removed from youth counterculture when it grew and came into being, but he was able to adapt into the booming counterculture and bedazzle a group of followers, primarily young women.

The subject of Manson’s charisma is a reoccurring theme throughout the film. Riveting first person detailed accounts of the so-called cult leader comes from those who were there. The names of the Manson women, Patricia Krenwinkel, Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, Susan Atkins, Linda Kasabian, are infamous. None of them appear as talking head interviewees in this documentary.

Missing pieces of the Charles Manson story are brought to the forefront with interviews with Diane Lake, who was a part of the Manson family, yet left before the Tate-Labianca murders.

More fascinating insight and inside information came from Philip Kaufman, an actor turned record producer who was locked up with Manson before he developed his following of “The Family.”

Kaufman acted as a linking conduit when Manson headed to Los Angeles, introducing him to movers and shakers of the day in the music industry. The two who were most prominent in Manson’s orbit were Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys and Terry Melcher, producer of the Byrds.

The rise of the counterculture of the late ’60s impacted the music of the day (and vice versa). The rise of a new vanguard, with the likes of Jimi Hendrix and The Doors shook things up, making the pop music of a few years before seem stale by comparison.

Wilson was looking to explore sounds outside of the Beach Boys’ established, trademark sound. He took to Charlie bestowing him with the handle of “The Wizard.” They broke bread at the Spahn Ranch, a secluded location outside of L.A. Manson wrote a song called “Cease to Exist.” The Beach Boys altered the song under the title of “Never Learn Not to Love.” Bits and pieces of both songs are in “Manson: Music From an Unsound Mind,” so the viewer can compare the them.

Manson didn’t share the same closeness with Terry Melcher. The story goes that Wilson and Manson shared a deep, sincere friendship. With Melcher, there was an association with the hopes of him hearing Manson’s music and helping to further push his music.

Melcher passed on Charlie’s music, which emotionally crushed Manson. Speculation is presented as to Melcher being the initial murder target, but Sharon Tate and Roman Polanski had recently moved into the house on Cielo Drive where Melcher had previously lived.

It was a killing like Los Angeles had never seen before. Terror gripped the city – months later Manson and members of the Manson Family were apprehended. Even during that time music played a part in Manson’s life.

In 1970, a couples months before Manson was on trial his “Lie” album was released, put together and distributed by associates and connectors on the outside. Philip Kaufman helped to release the record and on camera holds up an original pressing.

Charles Manson’s “Lie” album is as an esoteric anomaly. The sound of the album is listenable, enjoyable acoustic folk, yet the sound is not spectacular. The significance of the “Lie” album comes from who made the music.

I was quite surprised to find out via this documentary that part of the motivation for the release of “Lie” was to use it as a tool to convince the public that Manson was supposedly innocent and to influence the outcome of the trial.

It failed to catch on, no chart placement or widespread acclaim. Years down the road, the “Lie” album would become a sought after oddity, sought by those into underground sounds.

Manson’s “Look at Your Game, Girl” was covered by Guns N’ Roses, included as a hidden track on the “Spaghetti Incident?” album released in 1993.

I was hoping some content connecting Manson’s music to the interest of those from other eras would have been present in the film, but it wasn’t.

The interviews in the film weren’t limited to personal Manson associates, but also biographers along with editors and writers for “Rolling Stone” magazine. Their input helps to round things out, providing an historical context and analysis with the events in the movie.

The ’60s counterculture at large proclaimed a greater sense of societal openness and humanitarian love. “Rolling Stone” writer David Felton pointed out that these values were what allowed Manson to work his manipulative magic.