by Mitchell Brown

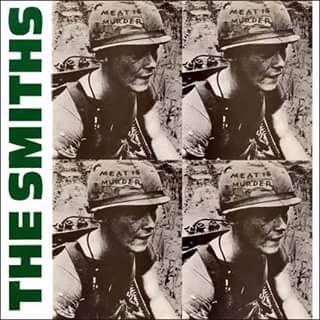

Last month marked the 30 year anniversary of the release of a musical masterpiece: The album “Meat is Murder” by the Smiths hit shelves on Feb. 11,1985. It became an alt-rock standard, one still championed by modern teens and twenty-somethings who were not even alive in 1985. Why? I tend to think music that transcends time is that which strikes a universal chord, a vibe, a feeling, a something that could be just as true in a future time as it was when first recorded.

Why does the music of the Smiths remain revered while many of the pop-culture artifacts from the 1980s are cherished only by those who were there to experience them as new? I think the answer can be found in the sense of universal reliability of the Smiths.

There are certain moments in life that are unforgettable, those golden moments, often from youth, that shine brightly. And for me, the forging of a musical identity was one of those moments. In my early teens, music became more than just notes and sounds, but rather an extension and reflection of the self.

I can pinpoint the forging of a musical identity to three songs: the Sex Pistols’ “Anarchy in the U.K.,” David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” and the Smiths’ “How Soon is Now.” With exposure to these songs, I was schooled on the fact that the alternative I was listening to had origins in decades past, and about eight years later I came to understand the greatness of the Smiths, along with Morrissey’s solo albums. Maybe it was because I was depressed, and listening to melancholy music became a form of therapy. But not all of the songs sounded like a funeral dirge, yet I can’t help but envision a gray skyline every time I hear the Smiths, and the ability to conjure such imagery connected to a song is a powerful thing.

And it’s no wonder that vocalist Stephen Morrissey and guitarist Johnny Marr were able to vividly sculpt such sonic images. Both were musical geniuses. When reflecting on the Smiths, Noel Gallagher, of the band Oasis, described Morrissey as the most literate man to ever do music, and I agree. An eloquent prose filled with pathos and passion that is reminiscent of literary greats of the past was found within the voice of Morrissey. I can’t think of another singer who was so heavily inspired by Oscar Wilde, let alone whose lyrical prose touches Wilde’s greatness.

Part of the greatness of the Smiths is that it all cut a little deeper, a lot closer to what love, life and loss often feel like, as opposed to a distorted teenage fantasy that is really just left over pop-culture backwash from the sock-hop days of rock n roll’s infancy. The Smith’s lyrics were something more mature. It wasn’t the simplistic doe-eyed puppy love of the ’50s. Sometimes their songs weren’t even a matter of love songs, but songs of love that never was to be. Such a sentiment is epitomized in “I Want the One I Can’t Have.” Unrequited love expressed in song had been a thing prior to the Smiths, but the song feels like an entrenched wall of division between two parties. It’s not a song about losing something. It’s a song about something that was never allowed to exist, which can be even more devastating than love gone wrong.

The exaltation of the Smiths is probably due to more than just the brilliance of Morrissey’s lyrics. Some if it can be attributed to the Smiths existing when they did, context. That which stands out garners attention. In the early 1980s, a synth sound dominated popular music in Britain: Human League, Depeche Mode and the like. The Smith’s returned to the basics: guitar, drums, bass, melody, song writing, turning something old into something new in the post-punk era and becoming an indie-rock institution along the way. There was a quintessential British-ness with the Smiths, sandwiched somewhere in between the Beatles and Oasis. Is that part of what makes the Smith’s legacy so enduring? It’s part of their legacy, but it’s just one factor of many.

The greatness and longevity of the Smiths is ultimately the relatability of the music, music that was felt, not just heard. To truly feel music in, an almost metaphysical, sense is a lightning in a bottle rarity. For me, it’s happened only a handful of times, Otis Redding, the Smiths, Morrissey, Joy Division, Black Flag. Every word, every note, every sound seemed to cut right to the heart. It was music as more than an algorithm and a collection of notes assembled into melodies.

I can remember the first time the needle dropped onto my used copy of “Meat is Murder. “ I would usually skip the first song, “Headmaster’s Ritual.” I had listened to it too many times on a best of CD, and I always thought Morrissey sounded like he was yodeling towards the end of that one. The album for me always started with “Rusholme Ruffians,” an up-tempo number, with undertones of a rockabilly bop to it, yet lyrically dour with lyrics about some type of loss. If I listen to that song and close my eyes, it feels like yesterday, and a visceral attachment remains. Its music attached to heartfelt emotion, not a contrived pseudo-emotion, and the connection is timeless. Somebody somewhere feels a certain way and is in need of a musical backdrop for their emotional state. The Smiths have always done it for me.